jean-michel BASQUIAT

keith HARING

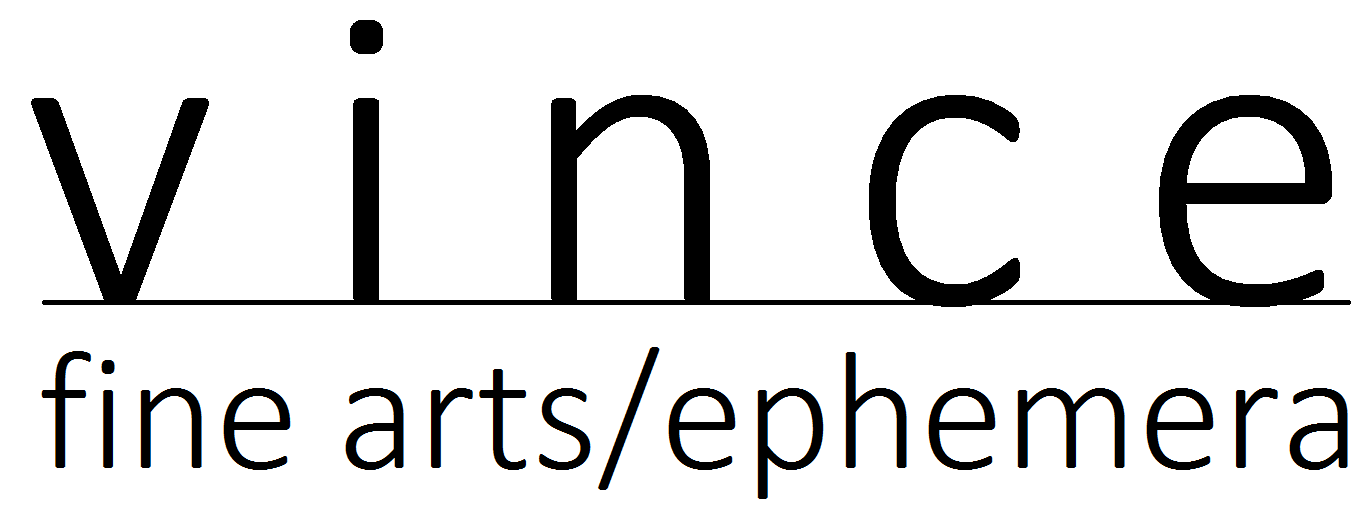

THE TIME SQUARE SHOW- "The First Radical Art Show of the "80s", 1980

FIRST REVIEW OF THIS HISTORIC SHOW, The Village Voice- Vol. XXV No. 24, written by Richard Goldstein, now-famous participants such as Jenny Holzer, Nan Goldin, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, and Basquiat were all just beginning their careers, and it was Basquiat’s first show as both the graffitist SAMO and a painter. NOT FULL NEWSPAPER- ONLY PAGES RELATING TO THE SHOW. Condition: Very good- age toning through out (see pics). Provenance: Estate Private Collection, NY Note: In the spring of 1980, sculptors Tom Otterness and John Ahearn noticed a “for sale or rent” sign on an abandoned building just off Times Square, at 41st Street and 7th Avenue. They were members of Collaborative Projects, Inc., or Colab, an artists’ organization whose approximately fifty members considered themselves social activists as much as artists. Several months earlier, members of Colab had worked with an affiliate group based in the Lower East Side, ABC No Rio, to mount The Real Estate Show in an abandoned building on Delancey Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan without permission of the landlord.

The artists broke into the building on December 30, 1979, more artists and community members joined them to stage performances and install artworks, and three days later the police evicted them at the bidding of the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (Committee). Although records were not kept to document the identity of the participants, the organizers deemed the show a success in terms of community outreach and involvement.

The intention had been to draw attention to buildings that languished decrepit at a time when the need for affordable housing was dire: city offices and landlords seemed to conspire in favor of future profits rather than address the immediate needs of low-income New Yorkers. Colab recognized the 41st Street building as another site from which to critique systems of power as articulated in the control of property. Times Square was a vital if seedy public space that Mayor Abe Beame had targeted for renewal. With the exhibition they planned, Colab wanted to speak to and for the neighborhood’s multi-racial and economically-diverse population of residents, visitors, and contributors to legal and illegal enterprises. They negotiated with the building’s owner Mark Finkelstein, who agreed to lend them use of the space for a month in June (Deitch 60).

Backed with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and a dozen other organizations, Colab solicited proposals for site-specific installations and received a landslide (Lippard 78).John Ahearn explained the appeal of the Times Square site like this: “Times Square is a crossroads. A lot of different kinds of people come through here. There is a broad spectrum, and we are trying to communicate with society at large” (Sedgwick 21). The Times Square Show would investigate how art could communicate across race, class, and gender divides and represent a complex urban identity. Colab organized the show with the founders of an alternative space, Fashion Moda in the South Bronx, and benefitted from their experience practicing democratic outreach. Times Square was a potent realization of late capitalist culture, where an economy of signs dominated. In such an environment, themes of sex and violence in a raunchy hand-made style were most likely to stand out amidst the cacophony of commerce. Paintings based on pulp novel covers, drawings of policemen, prints of dollar bills and rats, and life-casts of the disenfranchised: these rough and ready images communicated futility and desperation. Thus, The Times Square Show established a model for collaboration and a mode for addressing a broad audience that shaped the downtown art world of the early 1980s. Approximately one hundred artists contributed to The Times Square Show. Some were selected on the basis of their applications, others installed their work guerrilla-style in the unsecured building. There were no wall texts to identify the artists, who picked whatever available space appealed. Recognizable imagery dominated as did a do-it-yourself aesthetic; finish and craftsmanship were strenuously avoided.

The “Money Love and Death” room featured pictures of money, guns, plates, and rats as wall paper; The Times Square Show demonstrated the cultural possibilities that existed in the neighborhood already by attracting both art professionals and local workers through its doors. Unlike virtually all museums or commercial galleries, about half the participants were women and more than one-tenth were artists of color (Goldstein 31). Women and minorities were highly visible in the Times Square marketplace to a degree that they were not in the established art world institutions, so including their points of view was a sensible strategy for community outreach. Some women and black artists took the opportunity to engage in identity politics. Aline Mayer and Jane Sherry mounted a protest against violence against women which, they implied, was fueled by the pornography industry just outside

The Times Square Show’s doors and reiterated in language used to demean women. They hung nightgowns and dresses slashed with “CUNT” and “WHORE” in paint, alongside collages of porn magazine photos of vaginas. One compelling element in their installation was a girl’s frock strewn with candy nipples, which alludes to the sexual exploitation of children, the infantilization of women, and cultural pressure on girls to take on the accoutrements of adult women, all of which were concerns that occupied feminists. Other artists explored a sex-positive feminist politics as a strategy of empowerment. Erika Van Dam, in the persona “Chi-Chi” performed a striptease in The Times Square Show lobby, wagering that the art show context was sufficient to differentiate it from similar performances in Times Square strip clubs. One of the most powerful pieces by a black artist, noted by several reviewers, was Candace Hill Montgomery’s large, multi-panel drawing of a black man, beaten and lynched. It was framed in plexiglass and hung by chains from the ceiling, a striking juxtaposition of formal restraint and physical violence and a metaphor for racism (Deitch 63, Lippard 78). Alongside professional artists, untrained artists also participated, such as Willie (Bill) Neale who sculpted canes out of tree branches, and SAMO (soon to be better known as Jean-Michel Basquiat), whose gnomic graffiti were familiar sights on SoHo walls but here contributed an abstract canvas to the fourth floor Fashion Lounge (Goldstein 31).

FRAMING AVAILABLE